Passkeys to Drift

Passkeys

How are passkeys better than long-lived authentication cookies?

Rebase

Linus designed git rebase to make code review easier for himself, but very few projects operate the way Linux kernel development does. Why do most people rebase?

It turns out programmers use Git jargon imprecisely: reading rebase as squash, and merge to mean cherry-pick. Loose usage, unfortunately, makes it unclear what many commenters were advocating.

What do you mean? Why wouldn’t one rebase on master before pushing a PR? It keeps the history cleaner and more readable and unless someone else is simultaneously working on your branch it doesn’t hurt anyone.

—CM

This is a telling inversion; when do we need reasons not to do things? When they’ve become habits. Enough programmers must have a rebase habit that Fossil had to answer, “why not.”

One commenter was especially passionate; follow the links to see these in context, as I don’t think I can do them justice here.

There is nothing worse than a chain of multiple commits that lie outside of the linear history, and are just merged as a single change. You cannot “git bisect” through that to find a problem. When you try, you are taken into backwaters: a side chain where the individual changes exist, but which were never submitted to the trunk and are rebased to an old version way before the problem happened. That’s completely wrong; you need to be searching for a problem in the merged code.

A change consisting of multiple commits, if it is merged, should be merged individually, commit by commit. And that them becomes equivalent to a rebase. It is a rebase, plus parent information. Problem is, if you do that multiple times, it’s just too confusing to trace the origin.

Basically, git should not even have multiple parents for a commit. Multiple versions of a commit cherry picked into multiple places should be associated by a change-id header, not by parentage.

—KK

People rebase because the world doesn’t care that you wrote the code against an older version of the code base and then had to merge it against newer changes before publishing. What happened before publishing is your local problem in your repo that nobody should see.

—KK

If you’re editing a file, and make a typo and then backspace over it and write a new version, you have just edited private history.

If you have real-time, frequent editor backups, you could go into them and see the stuff you backspaced over; yet it doesn’t get checked in, not to Git, not to Fossil.

The author of Fossil is a kook who says that rewriting unpublished history is “lying”; yet he uses backspace like everyone else.

—KK

This is a verbal Jackson Pollock; all I see is a splatter of words, but these were some of the most-liked comments! I guess they’re likable because they leave room for each of us to read our own meaning into them.

Many commenters are fond of hiding the process (and assuming rebase means “squash”). Most succinctly:

I don’t need to see how the sausage was made.

—LJ

This is not an argument in favor of either rebase or squash. It’s claiming that squash is harmless, but if I ask, “Why do I need to eat my peas?” Would you say, “Your mastication doesn’t hurt me?”

I am trying to rebase as it’s so much less scary than force push :)

…

git reset HEAD~1 [iterate] git push -f—AL

A joke? Nobody really starts feature branches with reset HEAD~, right?

All told, the clearest reasons I see given for rebase came from the first comment: it asserts that rebase “keeps history cleaner and more readable.” Cleanliness, however, is in the eye of the beholder. Is a Mondrian better than a Monet? That thread leads only to endless arguments over semantics. Measuring “readability” is more tractable, but an operational definition requires we answer, “Readable for what purpose?” Thus, we return to the original question: Linus found rebase useful, but almost nobody uses Linus’s workflow, so for what purposes do most programmers rebase?

Value

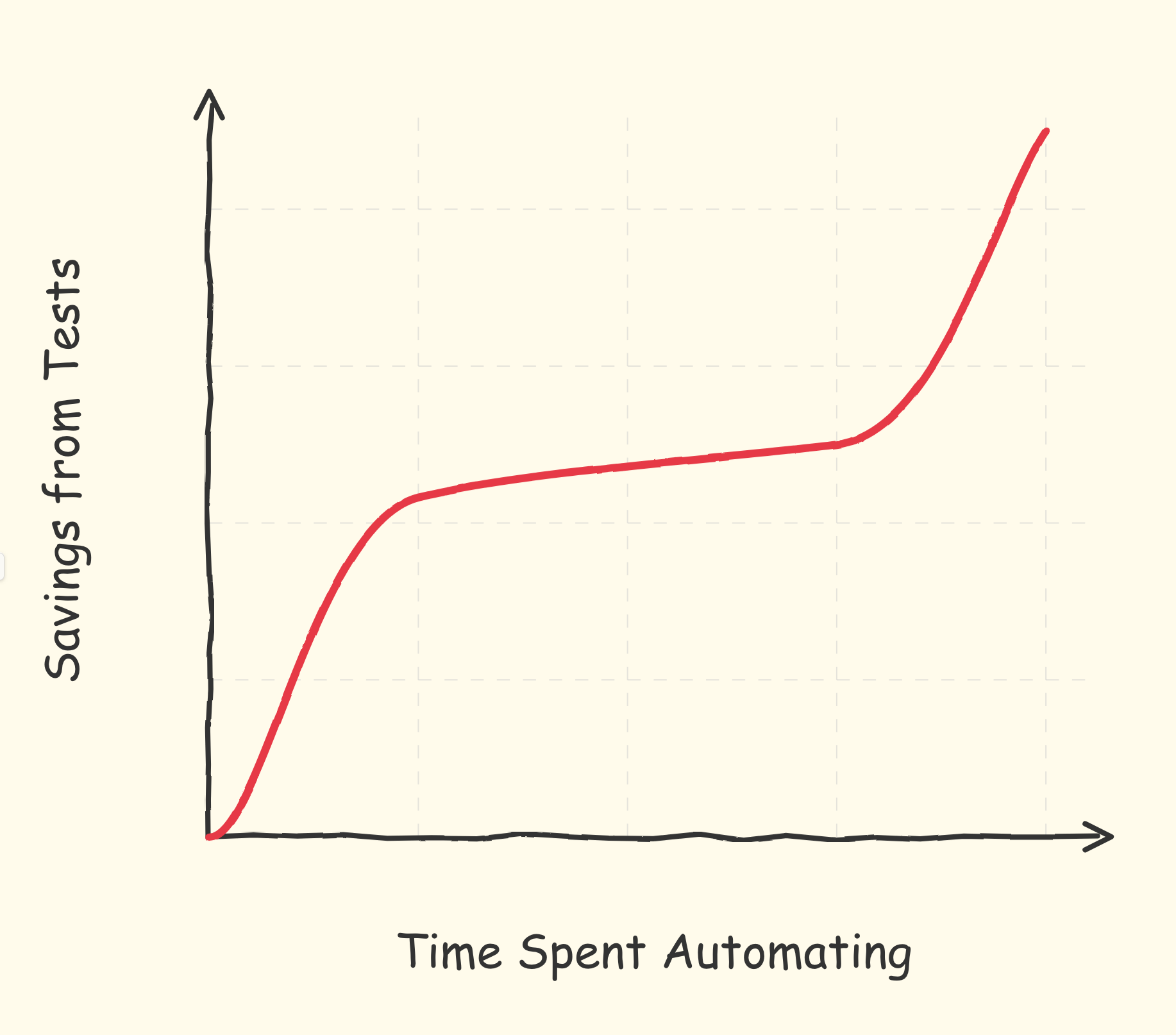

What if the value of the marginal test starts high, levels off in the middle of the coverage range, then increases again as testing become very thorough. At the margin, therefore, the most efficient amount of testing would be either very little or very much. Does this match lived experience?

Drift

Does semantic drift happen in programming languages like it does in natural languages?

The main example I can think of would be the drift that Vector has had over time in C++ and inspired languages. Went from being a specific scientific term to meaning a dynamic array.

It seems like it will still occur, but would be slowed by how long it takes the software ecosystem to adopt the drifted languages and libraries.

—BF

This is a good example; I don’t think “vector” has drifted within C++, so that’s not the kind of drift I had in mind, but it points to a clear example in Java: Java borrowed Vector from C++, originally with the same meaning, but the introduction of ArrayList shifted the meaning of Vector to emphasize its synchronization. This might be the exception that proves the rule: yes, semantic drift can happen within a programming language, but it’s hard to think of examples.