The update disease

There’s a pox on my phone. A little orange mark. A number. A message, “updates are pending.” If I itch it, an ooze of downloads.

On new phones, I immediately turn off automatic updates and I’m not alone; A significant minority of people probably have done the same. (About 7% in telemetry I see from Text Collector don’t run the latest version.)

Listen closely and you can hear computer people howling. “You need updates,” they say and so did I once upon a time, but no more.

Why do you hate software updates?

First, for me, updates usually make software worse. I’m not saying that software today is worse on average than it was yesterday, but that the software I use already does what I want it to do. I use it today either because I chose it for its good quality, or I have no choice because I use it for work. If the former, changes are more likely to make it worse than better — regress it to the mean. If the latter, at least it’s a devil I know. In most cases, therefore, an update is likely to be annoying to me. So, I turn off updates. If I can.

You always can, right?

Not in webapps, sometimes not in others. Samsung deserves a special dishonorable mention as they show an option, “remind me later,” which really means, “install later without asking.” That’s notably bad, but all consumer operating systems are guilty, as they now make it difficult or impossible to turn off automatic updates.

Because you need security updates!

Naturally, they say it’s, “for your safety,” and that’s partly true: many updates really are patching important errors that could let thieves into your devices.

We might wish programmers would just write software securely enough in the first place, but that’s impossible, no matter what Schneier implies that “experts” think: “the average nonexpert,” he says, “… need[s] to believe that an alternative is possible… And that will require creating working examples of secure, dependable, resilient systems.” And the examples he gives are, “Apollo’s DomainOS and MULTICS.” I wonder if it’s occurred to Bruce that not many people are looking for holes in software nobody uses.

Instead, consider Apache httpd. Various sites claim about a third of the Internet runs on Apache httpd, so bad guys want Apache vulnerabilities. Apache is 30 years old and the current 2.4.x branch just passed its tenth birthday. It’s as stable as software comes. It’s open source, so good and bad guys alike can scrutinize its internals. It’s small compared to an operating system and its developers seem competent. If anything has a chance of all bugs being found and squashed, Apache httpd is it. And yet, sixteen vulnerabilities were reported last year.

See, even given the best possible chance humans can’t write perfectly secure programs. You need those updates!

Don’t be too pessimistic. Apache Web Server still is very secure and very stable, and it’s unlikely any of those vulnerabilities affected you if you were running Apache, but these bugs illustrate that it’s impossible to ship a program with zero security problems. Updates, therefore, remain necessary.

Even though I turn off automatic updates, I do routinely patch the most exposed systems: operating systems, browsers and the like. I also take care to install as little as possible, jail risky programs, and don’t access my most sensitive accounts from my phone. This is all too much trouble for most people, and, reluctantly, I have to say that you’re safer leaving automatic updates on, for the security updates.

The security updates bring riders though, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Although forcing unwanted software on someone is a crime in the United States, you “agreed” to the trespass by clicking through the terms. Developers can include anything they like in updates, and our incentives are even worse than Schneier reckons: not only do most programmers have little reason to write secure software, we’re incentivized to create problems because more bugs mean you’ll need more updates.

But bugs also mean more work for them.

Exactly. Updates keep programmers in jobs. Imagine you’re a programmer in Silicon Valley: if you join a startup and build a robust product from the start, the founders won’t need you anymore. You’ll be laid off before the fat check.

Don’t employers want to minimize cost, so shouldn’t they hire programmers who make fewer bugs?

I can only speculate about what venture capitalists think, but I imagine that they accept this as a cost of keeping the Silicon Valley mystique alive.

In other cases, companies need to keep changing things so customers keep believing that newer is better. If people en masse were to notice that this year’s iPhone isn’t remarkably different from last year’s, Apple would quickly collapse.

For most companies though, software is now like accounting: they all need it, but how well they do it barely matters. I have subscriptions to both Netflix and Hulu; Netflix is far less buggy, but Hulu has shows I want to watch, so I keep Hulu. Why, then, should Hulu bother to improve their software practices? Even “tech companies” aren’t software companies: of five big ones you can name, only one makes a meaningful fraction of its income selling software. The others are a retailer, two advertising brokers, and a maker of fashion accessories.1

Still, a cost is a cost.

If programmers mostly knew how to reduce defect rates, cost might pressure them to do so. But programmers mostly don’t know how to reduce defects, because we follow Best Practices that evolved to eliminate those parts of the process that stop bugs — namely independent specifications and testing.2 For example, When I started programming, “nightly” was a best-practice cadence to deliver to testers. Today, the goal is to inflict software on users almost as soon as the programmer finishes typing — “Continuous Deployment.” Much of the history of software development Methodologies can be seen as programmers wrestling out of oversight.

Having eliminated meaningful checks on their work, it’s easy for programmers to adjust scope and quality, subconsiously, till they find the amount of bugginess that suits them; I’ve worked in more than one place that achieved an equilibrium where every bugfix created approximately one new bug.

I blame programmers, but managers are complicit. It’s a rare manager who asks for X to be done now and wants to hear, “The problems with X are Y and Z, so maybe we should think about it first.”

Aren’t fast iterations a good thing?

In moderation.

Ok, but none of this explains why open source projects push so many updates.

Github is a social network — no more, no less — and like every social network, optimized for shallow engagement. Projects that are stable, like Apache httpd, generate little engagement. They become infrastructure, and maintaining them becomes an invisible, thankless job.

In either open or closed source, the incentives push toward change for its own sake — glorification of the new, old wheel re-squared. We get programmers believing two obviously ridiculous things:

First, programmers think that “two years,” is “old.” The madness of this statement should be apparent to anybody who’s not a toddler, but Node.js considers three years “long-term” and Apple erases apps after age two3 and Google does much the same.4

Second, programmers believe that “software is never finished.” I’ve actually heard a programmer complain about how unreasonable it was that his client expected the product to be useful without the developers’ hand-holding. What if a plumber took this view? “I installed your toilet, but don’t use it unless I’m standing by.”

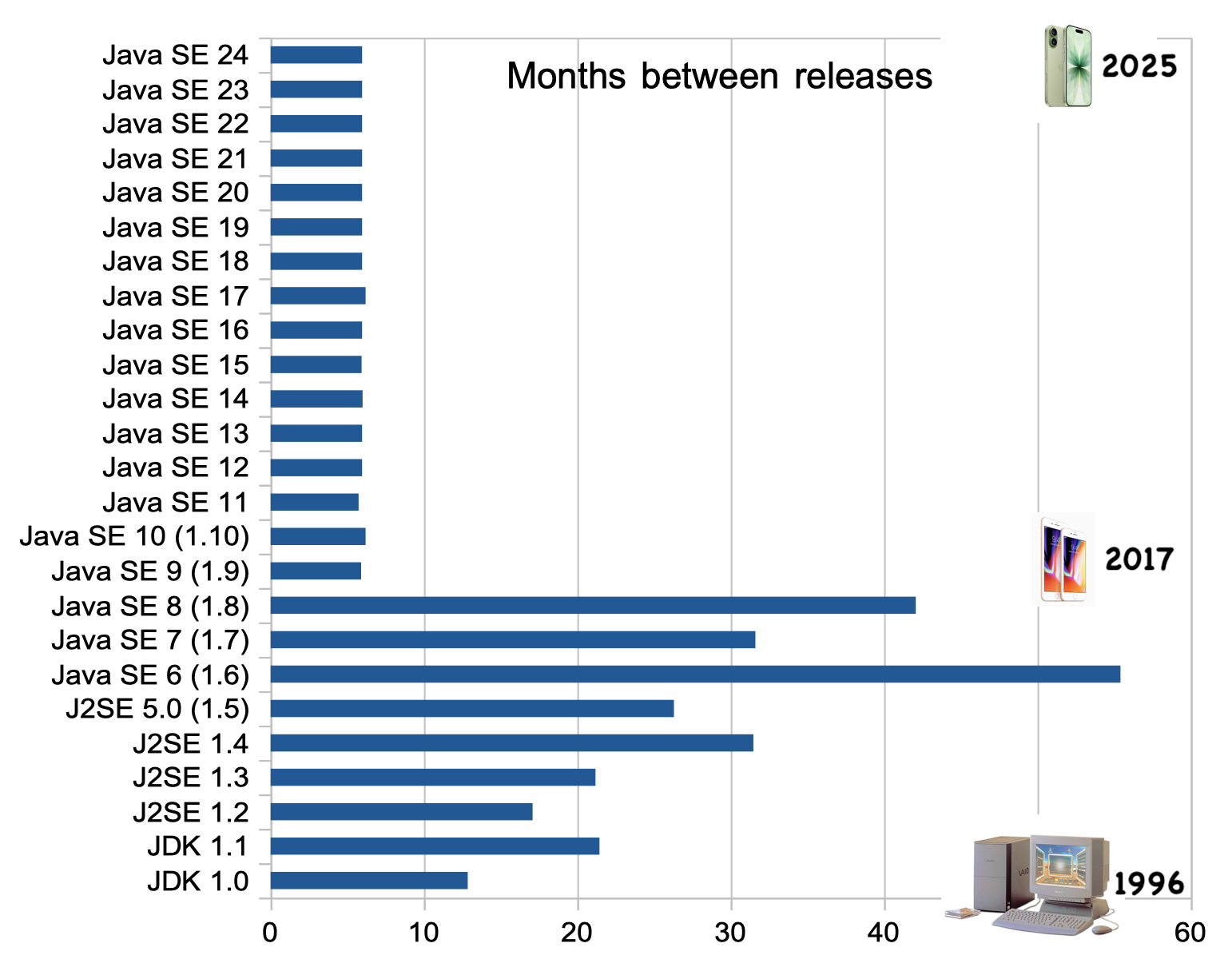

For a maturing product, we should expect frequent releases during an early shakeout period, becoming less frequent as it stabilizes; and that is what we see from the first 21 years of Java, from 1996, till Java 9 in 2017.5 After that, two releases per year. These release numbers are arbitrary, so this doesn’t mean Java changes accelerated in the last 8 years, but that Java salesmen believe they need to give the impression of rapid change.6

Until the 2010s, improving hardware pushed much software to change, to use the capabilities of smaller, faster machines. Today, however, I have computers ten years old that aren’t noticeably slower or bulkier than those I can buy new. Having lost the hardware impetus, programmers had to rely on Best Practices to make jobs. Ever more patches, ever more errors.

Can that change?

I hope the update disease is a phase — a kind of puberty the industry has to endure at the end of Moore’s law — but probably not. Since we can’t make totally secure software, users are at the mercy of updates. Legislation and standards like those from Nist try to dictate security, but just add bureacracy without any effect on security that I can discern.

Enclaves of developers sometimes push back — Sqlite’s 2050 support commitment is an honorable exception to the trend — but while the incentives push against stability, we can’t hope for a ground swell of developer sentiment reversing the tide.

Perhaps something like a warranty could make stable options at least available. Since we can’t make software “without manufacturing defects,” it wouldn’t be a traditional warranty, but a guarantee of security updates for some time, while keeping the rest stable. This is a bit like the business model of the Enterprise Linuxes, but such guarantees are rare in consumer products, and even for infrastructure like Java, the trend is toward instability.

Perhaps developers should bear more liability for what their software does. If you push damaging changes, I see no general reason you shouldn’t be held accountable just because the changes were in software. On the other hand, if I had to bear the liability for your losses in court if a judge didn’t like Text Collector’s format, I wouldn’t risk creating Text Collector in the first place. On the other, other hand, if phone makers could be held liable for damage caused by their policy of trapping messages, maybe there would have been no need for Text Collector at all. Ultimately, I cannot say whether increased liability for developers would be a good tradeoff.

But then, aren’t tradeoffs the heart of the question? Maybe we already got the tradeoffs right and today’s update frequency is optimal. If only one in ten people are annoyed enough to turn them off, maybe the other ninety percent are happy to have those updates. I prefer sliding a mechanical dimmer switch, while others prefer explaining to Alexa how bright they want the lights. I may not enjoy updates shoved in my cellular pipe every day, but maybe you do, and who am to say you’re wrong?

Notes

| [1] | In 2024 msft made up to a quarter of its revenue selling software. (See p61 for the definition of “product.” It includes hardware, but I bet that Xbox is the only significant hardware product and VGChartz estimates those sales at about 5 million units, substantiated by a separate estimate from Pure Xbox, so hardware is probably no more than 5 or 10 percent of the “product” revenue.) Software sales aren’t worth a mention for any of amzn (mainly retail sales and services), goog (advertising), meta (advertising), or aapl (iPhone). |

| [2] | This isn’t particular to software: many fields develop practices designed to insulate the practitioners from competition, but software is what I know best. |

| [3] | Screenshot in case the original disappears, since archive.org apparently can’t capture Twitter. |

| [4] | Apple and Google give only vague reasons for erasing stable apps. |

| [5] | Images of old computers from Sony Vaio PCV-70/PCV-90, iPhone 8 and iPhone 17. |

| [6] | Java’s Chief Architect argues for a faster release cadence. |